The Very Hungry Caterpillar: A critical analysis

On relatability and metamorphosis – analysing a classic text

Teaching critical thought

When I was a high school English teacher, it was part of the curriculum to teach kids essays. The intent was for kids to be able to document their critical analysis; to acquire the ability to pick apart a book, movie or any other “text”, to recognise techniques and themes, and to consider what the author actually meant.

I always thought it was a shame that so often the skills of critical analysis and essay writing were so tightly intertwined. An essay has value (I now spend a fair bit of time writing them for real), but it’s a cumbersome tool with which to start prising ideas from teenagers. The dense, highly structured conventions, the formulas, the acronyms, the walls of sentences – I felt like all this got in the way of the basic expression of ideas.

We spent much of our time studying novels, short stories or movies. If I was to do it all again, I think I’d focus more on critiquing the news, political speeches and leaflets, random rants on the internet; we did do some of this kind of work, but not enough. Rather than perfecting the essay, I’d prefer for my students to understand a valid source from a rubbish one; to be logical when appraising both sides of any given debate; to sift through rhetoric and fluff and get to the truth of the matter; to be able to call bullshit.

It would also bother me that our critical speculations weren’t entirely confirmable. We could only guess at what Shakespeare meant in Macbeth. It’s not like we could just ask him. I might have been the only English teacher who didn’t enjoy the prospect of a Shakespeare unit. My lack of enthusiasm may have been contagious.

Once, I blanked out the byline of a magazine piece I’d written myself, and handed it around for the students to pick apart and spot different literary techniques. Some of the students had already seen it in the weekend paper and probably wondered if I was just showing off, but it was interesting to hear some of the questions that did actually come up, prompting me to think: What did I actually mean there? Was I even in control of it?

We teachers were always seeking material that our students would find relatable; that they’d want to read and talk about. I would wonder: What might be the ultimate relatable piece of writing? One that everyone would surely know? The other teachers and I joked about doing a critical analysis of Eric Carle’s brilliant and popular book The Very Hungry Caterpillar. We never followed through on it though. Until now.

Before we dive in, a few answers to some inevitable questions:

- “Isn’t it the job of the teacher to bridge that gap between ideas and the ability to communicate it clearly? To build these skills in their students?” Yes. Yes it is. These are merely my impressions, from early in my teaching career. (Full disclosure: there wasn’t really any “middle” or “late” stage in said career.)

- “Is this a serious analytical essay?” About as serious as a first or second year university student writing something at 4am for a 9am deadline, for a book they didn’t actually read.

- “You better not be making fun of Eric Carle.” No, just a bit of fun with a classic book. Eric Carle is a legend. Also, technically this is not actually a question.

- “If you’re a serious writer, how come you don’t get published in serious publications?” True, this hasn’t yet been picked up by the New Yorker, but it’s surely only a matter of time.

Hungry hungry: Metamorphosis and ascension

Plot

The Very Hungry Caterpillar is a grand quest for the ages, akin to Harry Potter searching for horcruxes, Frodo Baggins inching towards Mordor, or the gnarly old guy from Jaws looking for the killer shark. This little caterpillar is on a journey of transformation, with the ultimate outcome of personal metamorphosis. He passes through the artifice of the manufactured world, sampling the fruits and processed goods borne from capitalism, before returning to the simpler, more natural environment, where he experiences relief and catharsis: “The caterpillar ate through one nice green leaf, and after that he felt much better.” The pinnacle of his quest is his literal and figurative transformation into a more elevated being.

Setting and structure

The opening is relatively humble and understated: a little white egg, at night, illuminated by moonlight. Carle foreshadows the impact this caterpillar is going to have on his environment, and indeed wider society, with the addition of the onomatopoeic “pop!” as the sun rises. Certainly this adds drama, given that the hatching of a caterpillar from its egg would normally make no audible sound.

The movement of the caterpillar through different scenes is circular: we start in the natural environment, then proceed through a parade of processed goods, perhaps from a picnic, supermarket or pantry: chocolate cake, pickle, salami, watermelon, etc. It is not explained how the caterpillar discovered or negotiated a frozen ice cream cone (did he gain access to a freezer?), and made an exact hole through its centre without being trapped in a quagmire of sweet, melted dairy goods. Carle knows when to show and when to tell.

We then return to the leaf, now in the daytime. It’s telling that here our protagonist finds relief – it’s a coming-home moment of renewal. He concludes by enshrining himself in his small house (his “cocoon”) ready to be reborn.

Carle was originally inspired to create the book’s structure when toying with a hole punch. The pages have physical holes pierced through the foods the caterpillar has partially eaten; plus some of the pages are really just folds, not full pages, and vary in size. Initially it was difficult to find a printing outfit which would take on the novel structure, but eventually a Japanese company agreed to the challenge. The caterpillar negotiated his own challenges, as did the author and publisher – but a way was found. Industrialisation (and later, digitisation) has elevated us to great feats, but Carle and his caterpillar might ask: Is it for the better?

Character

Carle originally intended for the protagonist to be a bookworm called Willi, but the editor thought a caterpillar would be more relatable. Carle agreed, in particular for the opportunity to include a butterfly in the narrative. This caterpillar is insatiable, driven, and not easily deterred by the magnitude of his task: to eat his way to what first looks like oblivion, but what transpires as redemptive transformation.

He does lose his way. He starts in the tree, but is then sucked in to what we can only imagine is the reckless frivolity of a picnic, or the wild excess of an overstocked pantry.

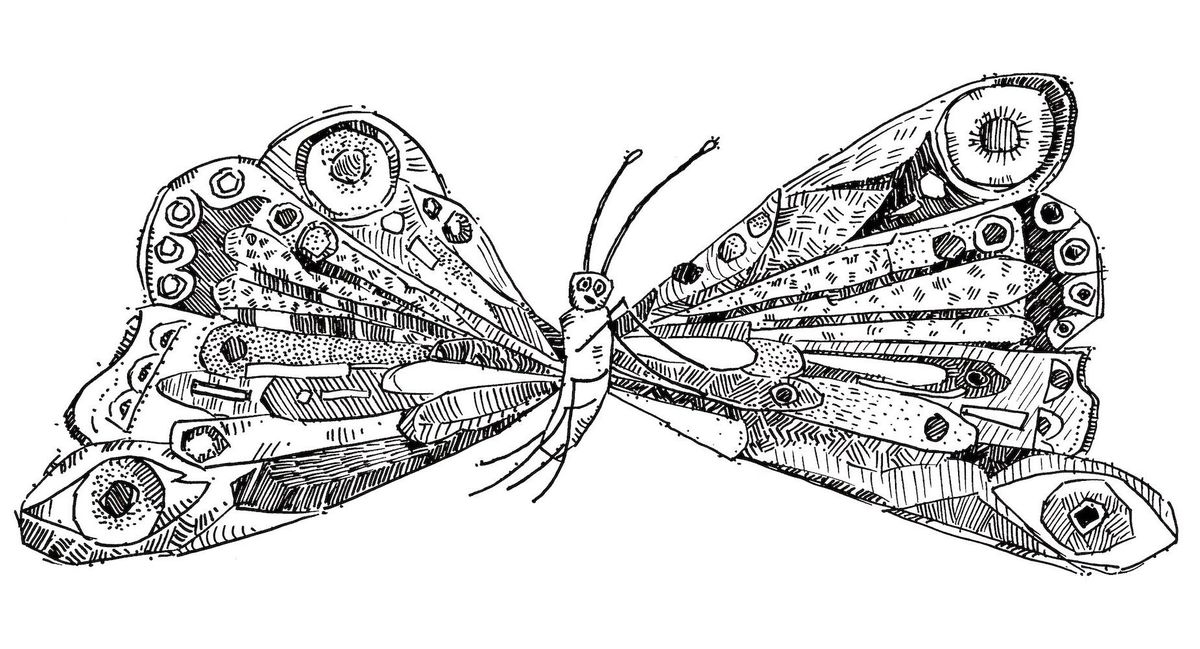

This transition challenges the moral fortitude of our protagonist. He must weigh the quandary of looting and stealing food to feed himself against the clear need for sustenance and survival. He chooses to indulge in the treasures he has pilfered, and feels worse off for it, both physically (“he had a stomach ache”) and emotionally, indicated by the relief he feels after coming out the other side of his food orgy. For this strength of character he is rewarded with metamorphosis into a more powerful being: a butterfly, capable of feats such as flying, far beyond the physical capabilities of the humble caterpillar – essentially a superhero or celestial entity by comparison. Carle emphasises the drama of this ascension with a colourful double-page illustration to conclude his masterwork.

Theme

One reading of this text is that it’s about class. Our caterpillar has a humble start, but via rich, processed foods, supported by the picnics and pantries of the wealthy, is thrust into a world of excess. You can see evidence of this in the way he just eats holes through vast repositories of rich food, rather than consuming it all, itself a comment on abject waste. This quickly feels uncomfortable to our protagonist; it’s only when he returns to his birthplace that he is able to understand there was never any need to compromise his core values.

Perhaps within this issue of class – or parallel to it – is the issue of childhood obesity. Our protagonist is quite literally unable to control himself around the rich foods he encounters, and eats himself into sickness. Ultimately he is able to reset his dietary course, recover from a depressing food stupor, and forge a more healthy path to adulthood, as well as a more streamlined form able not only to move more freely, but to fly.

The insertion of the cocoon at the end pits both religious and scientific thinking against one another. The caterpillar has closed himself within his cave, and we wait for him to arise and be born again. Yet Carle throws in the scientific exposition “He built a small house, called a cocoon”, asking young readers always to be more probing and analytical in their thinking. (Or his editor might have suggested he is more explicit about what he means by “small house”.)

Conclusion

Carle presents the world with a popular yet also nuanced and challenging text. The Very Hungry Caterpillar demands that we reconsider the relationship of the natural world with the machinations of human society. The caterpillar ate too much, and he felt sick – just as we risk becoming sick, overwhelmed or ostracised when we adopt overtly hedonistic or reckless philosophies. It’s notable that Carle has chosen a children’s book as the vehicle for such a powerful message, which itself implies that we should start forming and evaluating our position in society early – not wait for it to be formed for us, as we become adults and settle into a directional vector that we may or may not have actively selected for ourselves.

Comments ()