Your brother is not a towel

Spiders, scissors and sibling rivalry – learning how to get along (safely, if possible) with your family

“Your fairy just died,” my son Neko (9) says to my daughter Ida (5), and she starts yowling. “What?” Neko will say, seeing the frown on my face, throwing up his arms in a flimsy display of innocence. “Her fairy isn’t even real.” He is – at the moment, constantly – refining the time-honoured art of subtly needling your sibling in a way that’s defensible if challenged.

Ida can hold her own though, and can be just as annoying to Neko, if she feels it’s justified. “Get out of my room! I want to be on my own,” I hear Neko shout from the other end of the house. I go down there and see Ida sitting on his green suede couch, one leg over the other, smoothing a wrinkle in her tights, acting as though Neko doesn’t even exist. She looks up at me and says with utter decorum: “I can’t leave. I need to sit on a sofa, and there’s no sofa in my room. So I have to sit on this one.”

Neko plays on their developmental differences (ignoring that he’s four years older), like the fact that Ida isn’t reading at the same level; or he’ll try to quash her imaginative play with casual, cruel realism. Ida will leverage Neko’s righteous sense of justice and ownership, forever “borrowing” his precious things. As a parent, the bickering is maddening. I hope that some evolutionary benefit might shake out of these arguments: that Ida might learn resilience and confidence in the face of someone being a dick; that Neko might gain a greater sense of empathy.

Certainly they’ll need such skills later on. Home life is a proving ground for learning to get along with others in close proximity over a sustained period of time, but next there’s school, that battle royale of fragile friendship, group dynamics and, well, people being awful to each other; then flatting, where you’re bound not only by a living space but also bills; and then the workplace, where there are even higher stakes for maintaining your composure in the face of all kinds of behaviour.

My partner Vic worries that something’s wrong when our children fight. “Why don’t they just get along?” Vic has one brother, and apparently they had a harmonious sibling relationship growing up. (Can I get a fact check on this one, in-laws?) Over time, I’ve surveyed other people about relationships with their siblings when they were kids. Although some concur with Vic and say that they got along fine, more often people say that they fought, argued, schemed, kicked, punched, threw stuff at each other. The common line is: “We get along now, but when we were younger we were terrible to each other.” The words “sibling” and “rivalry” just seem to come together, like “jack” and “hammer”, or “machine” and “gun”. It’s less about whether there was conflict and more about the extent of it.

I grew up in Feilding then Whanganui, living with four other siblings: Stefan, Amanda, Angelo and Isaac (there’s also my brother John-Henry, who lived in New Plymouth, whom I only got to see sometimes). I’m a fair bit older than most of the group, and there’s a big age spread – Isaac is fifteen years younger than me.

There was conflict. The younger ones would argue and fight. This was mostly with words, but sometimes it was worse. Once, Amanda got so riled up by Stefan that she grabbed the nearest object – some heavy dressmaking scissors – and hurled them at him. They spun in a terrible, slow arc across the room and stuck three or four centimetres into Stefan’s knee with a thunk. We all just stood and looked at the scissors and the knee for a moment. The hospital had to use some special medical adhesive to glue the hole in his knee back together.

I tried to be a good big brother. The mediator, the mentor, the fun one. But I didn’t always succeed, and it could be stressful trying to keep the peace. Sometimes the younger siblings would form their own faction and gang up on me. Mum would be out of the room, and Stefan would shout, “Mum, Richard hit Angelo!” I’d look up in surprise, reading a book at the table across the room from them, and Mum would come in. “No I didn’t!” I’d say. Then Amanda would chime in: “He did. I saw it.”

We also had a lot of fun, and although it wasn’t fighting, it could be just as edgy. The opposite of fighting or rivalry is not necessarily harmony. A pack of unsupervised siblings, driven by boredom, will probe the limits and toy with danger.

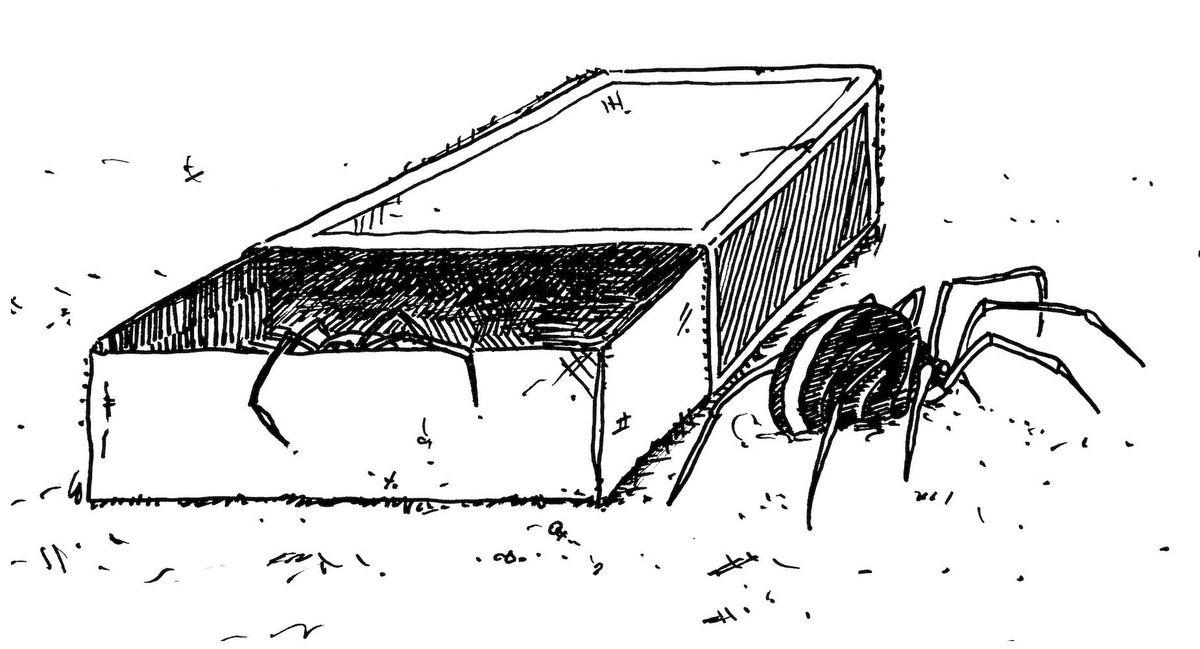

We did some stupid stuff, but we didn’t go as far as the previous generation. To listen to my dad’s stories about growing up on a Manawhatu farm with two brothers and a sister, they were constantly on the verge of killing each other, either through fighting or looking for fun. The boys would remove the shot from live shotgun shells, pack them with cotton wool and shoot each other, with real guns. They would play darts in the woolshed, but use themselves as the target, and attempt to dodge the darts – once, one of them got pierced straight through the cheek. The ultimate game for them was to stand in a field back to back, shoot an arrow straight up, and see who could be closest to it when it came down. This was all well and good, says Dad, until they lost sight of the arrow. I can only imagine what it must have been like to have been their parent. Once, Nana (their mum) opened up a matchbox in Dad’s room to discover it had been packed with katipō spiders (pretty much the only venomous spider in New Zealand).

I can’t remember whose idea it was to put Angelo in the dryer. I’m pretty sure it wasn’t my idea, but certainly it should have been my job, as the oldest, to put a stop to it.

Angelo wanted to do it though. He was probably only four or five, and eager to impress the others, who definitely wanted to see it, and were already jostling amongst themselves to determine who would get the next ride after Angelo. We thought it would be funny.

I closed the door and asked if he was sure, and he just said to hurry up and go. The instant the dryer kicked in and Angelo started spinning around I knew that it was a bad decision to put him in there. I’d made sure it was on the “Wool” setting, but even then, it looked uncomfortable when he turned upside down.

He only spun around a few times before I yanked the door open, and pulled him into a big hug to apologise. He was fine, just a little crackly with static. We did not play this game again. We did not mention this to Mum.

I feel bad bad about this episode, but I also feel like we were just following a sibling evolutionary pattern of rivalry, conflict and doing stupid, dangerous things for the sake of entertainment. Dad and his brothers came out of it all right. And there’s a story by David Sedaris about his siblings which makes me feel like the dryer – set to “Wool” – was pretty mild: On a snowy day in their neighbourhood, they had their little sister lie down on the icy road, both to teach their parents a lesson for ignoring them, but also to see if the cars would stop or run her over. That’s just straight-up cold.

There is, I think, a greater expectation within a family that you’ll forgive (or be forgiven) – because you’re related, but also because you have to keep living with each other, so you may as well make the most of it. I hope Angelo feels the same way. I apologise again, brother. We shouldn’t have taken the dryer for a spin. With you in it.

Comments ()