When you’re in your little room

Flatmates, rickety stairs and toiling in tiny spaces – a compendium of rooms and creative endeavours

I’ve typically lived in tiny rooms. A good friend of mine, Andy, thought it such a defining feature of my character that he placed “Little Room” by the White Stripes as the lead track of a mix CD he made for my 22nd birthday.

It started as a matter of economics. The cost of a room in a flat is proportional to the room’s size. My income while studying at university was proportional to the amount of time I spent in the workforce, which was either close to or exactly zero hours. On average, I was taking in about $150 a week, and rather than looking at that number and pursuing ways to make it bigger, I figured I just had to make my life as small as possible to fit. At the time, the starting price for many Wellington rooms was about $120. The rooms had to be small, and oh so cheap.

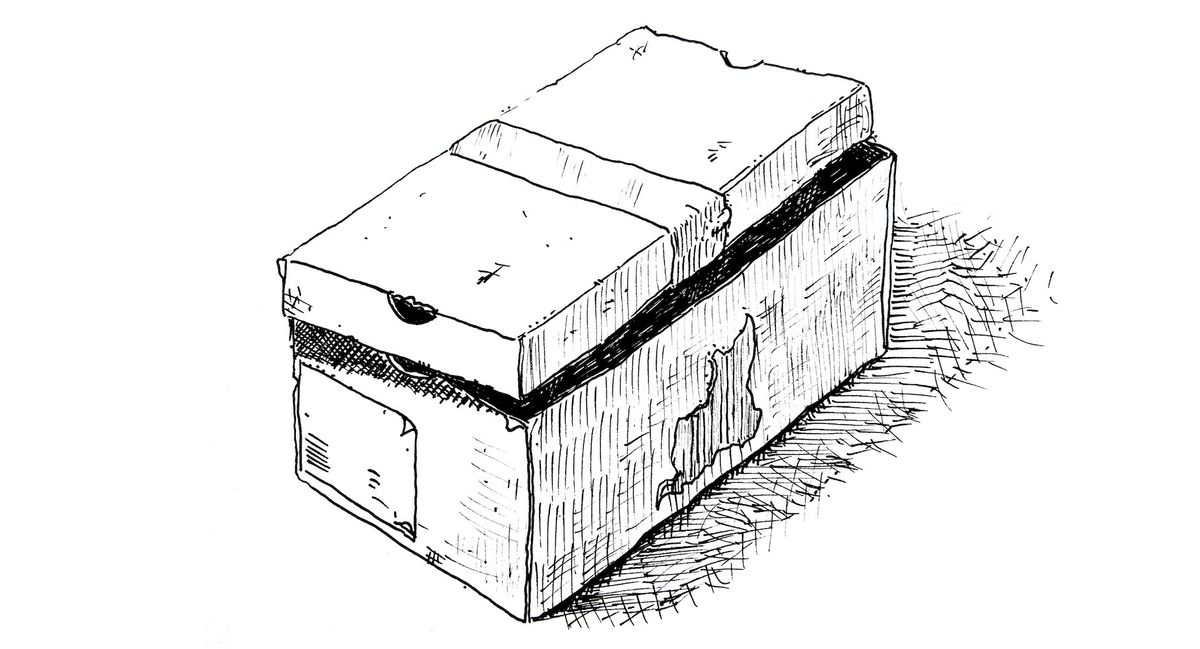

My small-room philosophy oscillated back and forth between being romantic (in the poetic, Beat generation, down-and-out sense – there was generally no space for intimate companions) and a fraction grim, like I was filed away in a shoebox in a house of full-size people in full-size rooms. But overall I didn't mind, and I have wonderful memories of my shoebox rooms and the people I lived with. A house is more than just a collection of rooms.

Birch Place

This wasn’t such a tiny room, but it was the room of my teenage years, which I shared with my brother Stefan. There was no door, not because it was open plan, but because the doors kept getting smashed off their hinges. Door smashing was a bit of a problem. My younger siblings could get quite angry, and the poor house often took the brunt of it. Mum solved the problem by not adding new doors.

I had a single waterbed, for some reason, which was a nautical novelty until the thermostat failed and it just became a cold pool of water with which to get hypothermia.

Weir House

In the year 2000 the cheapest rooms at the uni hostel Weir House were the double rooms, for $145 a week. That cost included all meals, power, heating, bedding, a desk, drawers, a wardrobe. And a roommate. I’d really only focused on the cheapness, and hadn’t contemplated what it might be like to spend a year in a relatively small room with someone you’d never met.

John Ross Pi Hooker, know to most as “Pi”, would tell me later, that when we first met in that room he had me pegged as a hopeless square (my words – only an actual square would express it that way). His arm swung around sideways for a casual hand clasp and I charged in with a ramrod-straight private-school handshake. We met awkwardly in the middle.

Rather than getting concerned at our initial differences, Pi made it something of a side project to make me less uncool. “The secret to dancing,” he would tell me, jumping on a bed and starting to slide around, “is in the arms.”

Did he succeed? You’ll have to ask him. It’s 2021, and we remain good friends.

Durham Street

Durham Street snakes from the bottom of Aro Valley in Wellington up into the hills. Near the top, up what felt like a thousand stairs that we had to climb every day, four friends from Weir House (Nathan, James, Chris, Hamish) and I assembled our first flat. It was a double-storey house, and we'd access the top flat via some wooden stairs that squeaked and popped and swayed away from the exterior wall.

We divvied up the room costs based on the size of our rooms, and decided on $70 a week for mine. We downgraded the cost (or, from a price perspective, for me, upgraded?) to $55 a week, after talking to the guy downstairs, who seemed disgusted that we might put a person in that room at all. In his opinion, it was more like they just put a door over the end of the hallway. The room was indeed a curio, pointed out as “where Richie sleeps” on grand tours of the flat. “Someone… lives here?” people would ask, their voices wavering with awe.

At a big flat party, we put a strobe light in there and had a micro rave. Pi was there, still trying to teach me to dance. It could fit about six people bouncing about on my bed, into the shelf, against the old primary-school flip-top desk, which was the only kind of desk I could fit.

I constructed a lot of bizarre industrial design creations in that room, including one that involved so much whittling of wood that the other flatmates woke one morning to find trails of wood dust leading to my room, and me, asleep, in a half-foot pile of offcuts and shavings.

Everything was very close: The walls to my head, my legs to the top of the desk, the bed to the window. I once slipped while leaning out over my bed and fell partway through the open, second-storey window. Chris saw me and shouted “Richie, no!” and grabbed me by the legs to pull me in.

Victoria Avenue, above George’s Fish and Chip Shop

Within a few hours of first coming to the little second-storey flat on Victoria Avenue, Whanganui, above George’s Fish and Chip Shop, my friends Kris and Andy barrelled in through the front door with a double mattress, which they’d found for me, driven across town on the top of a Mini, skidded up our sliver of an alleyway, and hauled up some rickety wooden steps overlooking a fish smoker. They were falling over laughing.

I shared the flat with Amanda, who was studying fashion, and Jaye, who was studying design. They were patient with me, even though I cooked the same thing – nachos – every week. Jaye described my cooking/kitchen demeanour as “hectic”.

The room cost $50 a week and was only moderately small on the smallness scale. You could probably even upgrade it to small-medium, or medium. It looked directly out onto the bricks of the neighbouring movie theatre. Every week on a Friday I’d go down into the fish and chip shop to see George, an old Greek guy with white curly hair, stern but sometimes showing a subtle twinkle of concern for his impoverished tenants. He’d pull out his accounts book, and write up a receipt for the rent payment, ripping out a carbon copy for me.

I was supposed to go to design school with Kris and Andy and basically everyone else I knew, but I flipped and flopped and faltered and didn’t end up pursuing it. Instead I spent days half-heartedly looking for work, starting terrible jobs and then quitting them, and drawing. I spent a whole month drawing a moose just because my brother found a picture of a moose on a t-shirt that he’d said he'd love for me to draw. My drawing style at the time was meticulous but terribly slow. Kris once told me that my approach was something like an old dot-matrix printer, scanning across from the top-left corner and ending up at the bottom-right. The fact that this approach took so damn long, and that I just couldn’t stand the picture by the end of it, put me off drawing for a good decade after that. (Nowadays, for the illustrations for this site, I only allow myself ten or twenty minutes.)

Riddiford Street

Cath, Steph, Alex and I shared a moderately dingy flat on Riddiford Street in Newtown, down a little alleyway and above what was then Aztec Cafe, where Cath and I both worked, on and off. The cafe owners gave us stale muffins at the end of the day. I would put milk on one or two and call it a meal.

The room was one of the smallest I ever had, and it came in at $65 a week. I wedged in an old “Viking” brand mattress I got from the Salvation Army store, and I had to sleep slightly curled, because I was taller than the room at its longest point. There was no bed base. I’d prop the mattress up against the wall every morning so that (a) it would air, and not go mouldy, and (b) to generate a couple of square metres within which I could move, eg for getting dressed. It was the most down-and-out I’d ever lived (I ran out of food completely a few times), but I was obsessed with Jack Kerouac and the Beat generation at the time, so it felt in theme.

I would get up very early in the morning and start writing/studying immediately. I had decided that I wanted to take on an entirely new major (English lit), skip all 100-level papers (I had to convince the uni, but I can be very convincing), and do all 200- and 300-level papers in one year. It was about a 175% workload, and I did it, and yes, it was a stupid idea.

At around 7:30am the flat would start to smell like it was burning down, because Cath, Steph and Alex were all straightening their hair. They all had slightly wavy hair, but insisted their hair should be straight.

During a heavy storm, water started leaking down my walls, threatening to breach the casing of my Mac that was so old it didn’t even connect to the internet or support USB (I had a pile of floppy discs). I rang the landlord, Stan, and although he complained and huffed, he came at 8pm that night, and looked at my walls, and said: “The window. It’s open. You need to close the window.” Oh yes, I admitted, I did need to close the window. I closed it and the rain stopped coming in.

The dining nook, present day

I don’t flat anymore; I bought a house in Paraparaumu with my partner Vic and our kids, Neko and Ida (and a cat, and a dog, and 9 chickens). It’s a small, cosy fifties place, and my favourite room is our little dining “nook” off the kitchen. Maybe it’s all those years of tiny rooms, but I like the enclosed feeling of it, the warm light, the view of ferns out the window.

Maybe it’s the antidote to the open-plan aspirations of most workplaces these days. It might seem weird to say, but if I couldn’t have a work office, then I’d probably be pretty happy with a cubicle. Not a fan of the open plan.

You might have to think of how you got started sitting in your little room

Whenever people ask about one of my little rooms, there was often a mixture of bemusement and concern: Why would you squash yourself down so small? Are you okay, concertinaed like this?

I didn’t actually spend all my time in these rooms. Because they weren’t spaces you’d invite people to share with you for any length of time, they didn’t isolate me, but instead encouraged me to push outwards and be social. And I enjoyed coming back to the minimalism of these spaces.

People worried that the walls would be constraining (especially for someone quite tall) – but it actually turned out to be the opposite. I had a lot of good ideas in those little rooms. I toiled away. I was industrious. Stuff got done, eventually. Constraints aren’t inherently bad. They form the borders within which you can be creative, the edges of the page – otherwise you’d just be drawing forever, like I used to.

Comments ()