Notes from a small house I

Inexact questions, kids being lawyers, an avalanche of artwork, and a forlorn-looking dog who can’t make up his mind

The key to an accurate conversation

My partner Vic can make you work for your answers, particularly if your questions are inexact. I’ll often lament that our house keys are always partly lost, which Vic will contest, claiming she knows exactly where they are. To which I will counter: but the location keeps changing, a location only known to you, so they are essentially lost to me. To unlock the location of the keys, we must utter the following words.

“Hey Vic, do you know where the keys are?”

“Yes. I know where they are.”

I always pause here, because I’m waiting for the location to be revealed, but Vic will not reveal it, because that’s not the question that I asked. Eventually, after seconds pass, I’ll have to continue.

“Could you please tell me where the keys are?”

“Of course. They’re in my purse.”

Another pause. We’re almost there. So close.

“Could you please tell me where your purse is?”

“Yes. It’s on the top of the bookcase.”

Passive tense evasive action

My son Neko has discovered that he can use passive language to try and absolve himself of any responsibility for wronging his sister Ida, or at least make his involvement appear ambiguous.

It’s never: “Sorry, I offended Ida.” It’s: “Ida has been offended.”

It’s never: “I pushed Ida, sorry.” It’s: “Ida has been hurt.”

If there’s no subject to the sentence, Neko has concluded, then was there ever a crime?

Always one step removed, always slippery.

Maybe he’ll become a reporter. “All we know at this time is that Ida has been offended. Stay tuned for updates.”

Or a lawyer. “My client can confirm that this person has been offended, but that’s all he can acknowledge at this time.”

The artist and the archivist

We’re big drawers in this house. My children are forever sketching invented characters and wild scenes, entire worlds edged with black pen and rainbowed with felts. This means we have paper everywhere: piles of drawings falling off edges, cats chasing sketches lying on the ground, fridges and doors with so many pictures hanging off them when a breeze slips through the house any work not fixed securely enough (there are never enough magnets for the fridge) starts flying around the house. Yes, it’s busy and messy, but it’s also a house full of art, which gives me great joy.

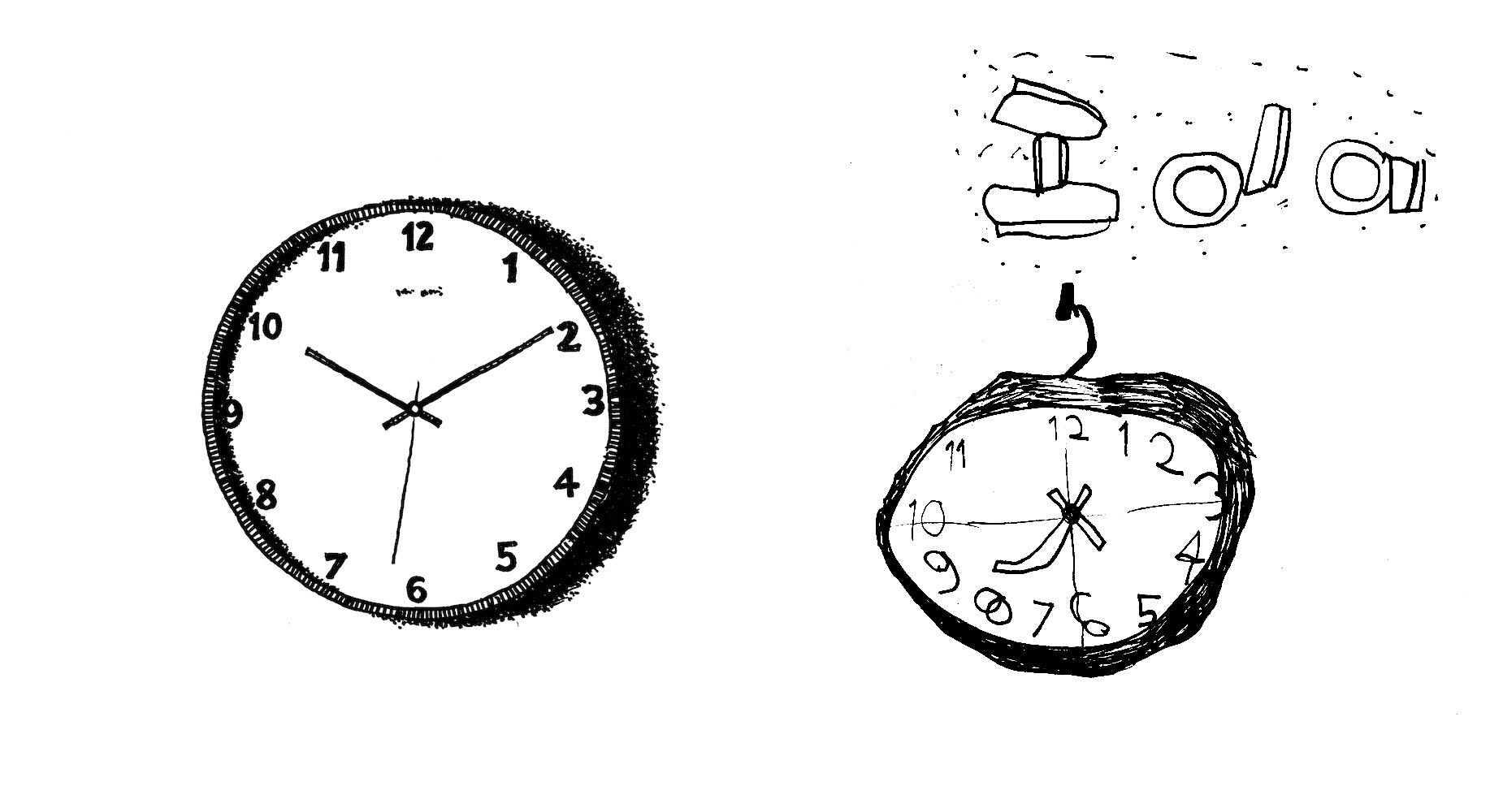

Saturday morning is my favourite creating time, when I’m typically creating an illustration for the latest blog post. That’s when you’re most likely to find the three of us – me and my two kids – drawing together at the table. I love that they’ll watch me draw something and then either try to draw the same thing or go and find their own still-life to draw (I tend to draw a lot of household objects). The other day I was drawing a clock, and Ida spent days after drawing all manner of her own clocks. I even see Ida watching what Neko is drawing – he has invented an entire fictional world populated by what he calls “nobos” – and adopting elements for her own work. While Neko treats such mimicry not as flattery but as flagrant copyright infringement plain and simple, and is critical about Ida’s theft of his intellectual property (which comes paired with absurdly specific style guidelines that no one save for Neko could ever live up to), it’s still heartwarming to see all of these ideas and images flow backwards and forwards between us, from one page to the next.

The first slight downside to this prolific artistic output is that it can turn a little competitive. I work from home, and often either Neko or Ida will bring what they’re working on to my desk, and ask me to declare which of the characters or elements they’ve drawn is my favourite, and then my next favourite, and so on – essentially to stack rank everything on their canvas. It puts me in a bind, because I don’t want to diminish any part of their creation, and also they generally have one they want me to choose (their own favourite) and can get disappointed if I don’t guess right. The worst is when they both come to me at the same time, a subtle ploy to try and get me to say whose artwork I like more.

The second mild issue is all of the archiving. Where does all the work go? It’s important that the work is valued, but we often run out of fridge, door and wall space to display the latest and greatest. While Vic’s a fan of the artwork in the moment, she’s not a fan of the art being everywhere, in piles on the table, underneath the fruit bowl, or wedged between house plants. I do not recommend that you hire Vic to work at your art gallery. (“Where did all my work go?” a local painter will ask, crestfallen. “Gah, there was just so much of it I had to do something about it,” Vic will answer, “But look how tidy the gallery is now!”)

So now, after we’ve appreciated a selection of the kids’ work for a limited time, I date and name it, take a picture, and add it to a growing digital archive of their work. That in itself takes time, and is not without incident: on more than one occasion I’ve taken a pile of art outside to snap some pics in the good sunlight and the wind has whisked the pages away, transforming the job into a frantic neighbourhood art treasure hunt. I plan to batch the drawings into months and years, then bind them into a book and put them on the bookcase, a record of artistic development over time.

Now in the future, when my kids are all grown up, they’ll either appreciate this a great deal, and feature their favourite early artwork books on the coffee table; or they’ll joke to their friends, after I’ve stopped in briefly to visit them, with a long beard and a wild, red look in my eye, on my way to the new second storage unit because the first one is chock full of paper, that they don’t really get what Dad’s on about, but they do love that mad old librarian, either way.

The forlorn

Our dog Teddy doesn’t bark when he wants to go outside. He’s really not much of a barky dog. He just stands at the front door, which is made of glass with a stag in a woodland clearing etched onto it, and looks back, silently, hoping one of us will notice him looking and correctly interpret his facial expression.

We can easily understand that dog standing in front of door generally means dog wants to go outside, but as far as interpreting his face, we don’t have a great deal to go on. Teddy just always looks sad. He isn’t actually sad all the time – he has a pretty sweet life, all things considered – but he just looks that way. Something to do with his long poodle/labrador/retriever nose; the deepset brown and orange eyes; the limp, floppy ears; the curly hair that grows over the top of his brow, forcing him to tilt his head upwards so that he can peer under the fluff.

I’ve had people say that we should just get a dog door, so we don’t have to let him out, so that he can just come and go as he needs. Trouble is: The door is made of glass, and for a dog Teddy’s size (the big poodle genes are strong) I imagine we’d need something more like a stable door, where the whole bottom half can open out.

So, at least for now – well, probably forever – the moments before the opening of the door will be tinged with melancholy, as the dog looks out at the starry night outside, and the streetlights project the stag on the glass on the hallway wall, and I’ll anticipate that my poor, sad-looking dog wants to go out for a wee, and so I, the caring owner, will let him out, and there’s a rush of cool night air as Teddy trots through the door. I then close the door because it’s cold, but seconds later Teddy’s back at the door, on the outside, forlorn, looking in, so I figure he didn’t actually want to be outside. Then once he’s inside and I’ve closed the door, he stands once more at the door, looking back, so sad, so I let him out. Then he wants to be let in again. Then out again. And so on.

Comments ()