Lucky ducky

The terribly irony of trying to do the right thing but making things much, much worse

At the northeastern end of Whanganui Collegiate School there’s a little lane which ends at Liverpool Street. When I went to school there, this was where the “day” students (as opposed to the boarders) would get picked up.

I lived in Aramoho, a suburb across town, and generally I’d bike to and from school. But from time to time I needed Mum to give me a lift, so I’d mill around the hedges at the lane entrance, with the other boys waiting for their parents.

Today I was waiting there with three boys from the year above, Adrian, Jake and Trevor. They smiled when they saw me set down my bag to wait.

“Does your car have electric windows?” asked Adrian.

“No,” I sighed, “it has a handle you crank to make the windows go up and down.”

“I didn’t know they still make cars like that,” said Jake, joining in.

“I guess they do,” I said.

A slick, modern car (an Audi, I think? I wasn’t good with cars) glided in to pick up Jake. There was a pause in the conversation as Jake left.

“Where are your Christmas lights?” said Trevor.

“They aren’t Christmas lights,” I said. “They’re safety lights, for biking at night.”

I wondered how they knew about my highlighter arm and leg bands with blinking red LEDs. I usually waited until I was well down the road before pulling over and putting them on. Someone must have passed me in their car.

“They look like Christmas lights,” Adrian said.

“Well, it’s July. You’re a little early,” I said. I rarely had good comebacks for these guys. I’d only think of them on the way home.

The chatting faded off because we could all hear the deep whining strain of an engine navigating the hill, about a block away. Adrian and Trevor started to laugh.

“Looks like your ride’s here,” said Trevor, patting me on the shoulder.

We watched the orange Vauxhall Viva slow, then do a U-turn, exposing a single green door on the passenger side. Mum waved from the driver side, and I got in, my face burning.

I didn’t know what year the Viva was made exactly, but in 1997 it seemed practically an antique.

“Friends of yours?” Mum asked, as we pulled out onto the road.

“I wouldn’t say that,” I said.

- – — – -

The sense of being an underdog, a scholarship kid at a poncy establishment, is at least partly what drove me to be embarrassingly righteous at high school. I worked obsessively, agonising over test scores which were already plenty high enough. I offered an answer to every question in class. I didn’t swear, ever. I was never late.

Every Friday, Whanganui Collegiate School would publish and distribute what was known as the “blue sheet”: a list of all the people who had received punishments (drills, sports drills, tardies, tickets) that week and the reasons the teachers had allocated for each. I never once appeared on it.

I did talk back to a teacher once – but this was in itself a moment borne of righteousness. Mr Tait, our English teacher, had been listening to the other boys call me a nickname I detested: Bert. It sounds an innocent name, but it came with nasty connotations built up over years within the school milieu. You did not want to be a “Bert”. And every year someone was assigned it.

Mr Tait turned casually towards my desk, his moustache twitching into a smile and his eyes mischievous.

“What do you think about that… Bert?”

Every single person bar me roared with laughter.

My eyes went red. It wasn’t just the injustice of a teacher joining in on the daily heckling, but the fact that this was a teacher whom I admired very much. I normally loved Mr Tait’s English class. The laughter started to die down.

“Oh I don’t know… TURKEY,” I spat back.

Everyone immediately stopped laughing. Although I felt like I was going to catch fire, the reaction was incredibly satisfying. It was customary for the boys to say awful things to each other all day – but no one had dared call a teacher by their nickname to their face.

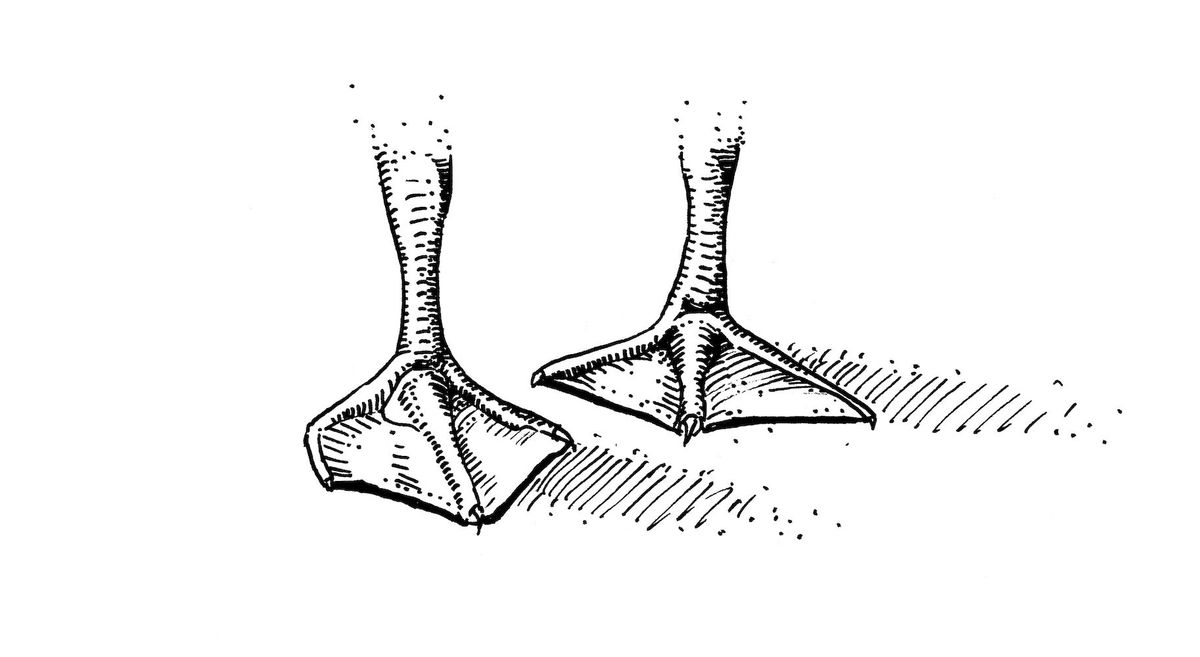

The nickname “Turkey”, as far as I understood it, referred to Mr Tait’s slightly odd gait. I wasn’t sure if he knew of his nickname beforehand, but the look on his face confirmed that he did. Mr Tait and I glared at each other, locked in a stalemate. Then he just proceeded with the lesson, ignoring me. We never spoke of it again.

Alongside sports, arts and academic concerns, school was a place where you were sent to learn how to deal with dicks. It was part of the curriculum.

- – — – -

One Saturday, our family took the Vauxhall Viva on a roadtrip. Destination: Palmerston North. We’d taken State Highway 3 out of Whanganui many times; the road winds up through expanses of farmland, passing turn-offs to Lake Wiritoa and the local prison. As we neared the crest of one of the steeper hills, I saw that a mother duck was walking her ducklings across the highway.

It wasn’t going well.

This was a 100K zone, and a stretch of highway where there was little time for drivers to react. The ducklings were just too slow, and oblivious to the danger. They’d just pop as the cars ploughed over the top of them.

“Stop the car!” I yelled to Mum.

“What? Why?” Mum said.

“Just do it. Please!” I said.

We weren’t going that fast – the Viva really took the hills hard – but Mum still had to take fairly drastic action to pull onto the shoulder.

While I waited for a gap in the stream of high-speed traffic, another duckling popped, then another. I raced out onto the road, and managed to scoop up one duckling and zip back in time to avoid the next car myself – narrowly. The driver of the car honked and gave me a look I probably deserved. My heart felt like it was going to wrench itself out of my chest, it was beating so hard.

I got back into the car and Mum gave me a strange look. She was probably wondering why this teenage son of hers, who had shown no special affinity for animals thus far, and actually actively disliked the cats (we had a glaring of half-feral cats – they’d jump onto the table and try to steal food off your plate while you were eating it), had just risked his life – and, basically, everyone else’s – for a duckling.

Right then, I felt it was important and the right thing for me to try and save those ducklings. I found an old bike helmet amongst the car junk, and put the little furry duckling into it, which looked pretty unemotional about the current state of things. It ruffled its wings and closed its eyes.

My younger siblings craned forward in their car seats to take a look at the new member of the family.

“Aw, it’s cute!” said my sister, Amanda.

Outside, the last ducklings popped and the mother duck just waddled into the bush on the other side. I wondered if she was experiencing regret, or just wondering where all the kids went.

- – — – -

There was some road work going on along a section of the highway before Bulls; the traffic was reduced to a crawl over the loose rocks. We were behind a large cattle truck. Just as we were about to move back onto the paved road, there was a sound like a cannon being fired, the windscreen exploded, and instantly the interior of the car became a howling, whistling wind tunnel, with food wrappers and receipts whipping into our faces. That must have been some rock the cattle truck flicked back up at us.

For the second time that day, Mum pulled the car over in an extraordinarily calm manner, given the circumstances. We took a look around the car. We were ankle deep in cubes of glass. The kids in the back were okay; they had mostly been protected by the front seats. Mum had been wearing glasses, which saved her eyes; apart from a few scratches on her arms, she was okay. I’d been looking down at the duckling, so most of the glass had flown over the top of my head and down my sides; some of the cubes had gone down my shirt, but apart from that I was fine.

We pulled into a nearby service station and scooped out the bulk of the glass; an attendant helped us fit a temporary soft-plastic windscreen, which did an acceptable job at low speeds, but became unbearably flappy and loud once we hit top velocity. If you’ve ever spent time inside a tent during high winds, then you’ll understand what the trip back to Whanganui was like.

The duckling poked his head out from the helmet, to see what all the new noise was about. I wondered if he might consider this an out-of-the-frying-pan-into-the-fire type scenario.

- – — – -

Back at home, I had to take care to keep the duckling away from the hungry feral cats. I kept the duckling (I wasn’t sure of its sex) in the room I shared with my younger brother Stefan, and experimented with different foods it might eat, outside white bread. Rice Bubbles and Cornflakes seemed to be decent contenders. White carb’s: the natural food of the duck.

I imagined my duck growing to full size and waddling around the yard, perhaps taking a dip in the stream out back, but always returning home at the end of the day. How big would it need to be to hold its own against the cats?

The next day was Sunday, and we had to go to church. I wasn’t sure why we went to church, but as a family we were going through a stage where that was something that we did.

On the drive into town, I quizzed Mum about our future pet duck plans.

“Do you think we could train it to come back, if it eventually flies away?” I asked Mum.

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Mum, trailing off.

On the way back from church, I started thinking about school the next day, and what the duckling was going to do while I was at school. I also started thinking about the door to our bedroom, and whether I’d remembered to close it.

Everyone helped me search for the duckling when we got home. But we only found parts of it: the bill, and some flippers.

None of the cats tried to steal any food off our plates that night.

- – — – -

I was devastated at the intense irony of saving this duckling from a quick death only to explode broken glass over it and then leave it to be eaten alive by a glaring of half-feral cats. I couldn’t stop crying for about ten minutes. But then I had homework to attend to, so I just had to move on.

A few days later I was getting onto my bike at the end of the lane outside school. I hadn’t noticed that Adrian was standing there, in the gloom of the early evening.

“Not getting picked up tonight?” he snorted.

“No, the windscreen got smashed, and it still needs to be fixed,” I said.

“Hard luck!” said Adrian, like it was an accusation. And it was true, far too true.

Comments ()